Today in history

+7

Tommy Two Stroke

ramiejamie

Admin

nordic

Lolly

gassey

Weatherwax

11 posters

Page 10 of 35

Page 10 of 35 •  1 ... 6 ... 9, 10, 11 ... 22 ... 35

1 ... 6 ... 9, 10, 11 ... 22 ... 35

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

12 th February1993

James Bulger abduction :

Two-year-old James Bulger is abducted from New Strand Shopping Centre by two ten-year-old boys, who later torture and murder him.

In February 1993 two year old James Bulger was abducted and murdered by two ten year old boys Robert Thompson and Jon Venables. James Bulger went missing while out shopping with his mother in Bootle’s Strand Shopping Centre on 12 February 1993.

Thompson and Venables led James Bulger away from the shopping centre while his mother was in a nearby butchers shop. The picture, captured on CCTV, of James Bulger being led away by hand was to become one of the most infamous images of the case.

After murdering James the boys left his body on a nearby railway line where it was discovered two days later. The investigation was led by Detective Superintendent Albert Kirby. After their arrest and throughout the trail the boys were known only as Child A and Child B.

In November 1993 Thompson and Venables were convicted of the murder of James Bulger. The boys were named by the trail judge Mr Justice Morland and sentenced to secure youth accommodation with a recommendation that they serve at least eight years in jail. In June 2001 Thompson and Venables were released on life licence and given new, secret identities.

The details of the murder that emerged during the trail shocked many people and led to public outrage, particularly in Bootle and Liverpool.

After abducting James the boys had walked him for two and a half miles. They were seen by 38 people, some of whom challenged them, the boys claiming that they were looking after their younger brother or that James was lost and they were taking him to a local police station.

Since their release an injunction in England and Wales has banned reporting of Thompson and Venable’s new names and their whereabouts. Although the ban does not apply in Scotland, or other countries, and despite numerous rumours their identities have remained secret.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

Thanks for these history posts gassey, they make interesting reading for our members. Keep up the good work.

Lolly- PlatinumProudly made in Wigan platinum award

- Posts : 36745

Join date : 2019-07-17

Age : 53

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

13 th February 1961

The Coso artifact :

An allegedly 500,000-year-old rock is discovered near Olancha, California, US, that appears to anachronistically encase a spark plug.

The Coso Artifact is an item known as an “out of place artifact.” Out of place artifacts are essentially modern objects found in places where they do not belong, hinting at the possibility of modern technology having been around long before modern man developed it. In the case of the Coso Artifact, the item was found inside of a stone or lump of hardened clay.

Proponents for the Coso Artifact say that the material in which it was discovered is too old to have held such an item. Estimates put the material at around 500,000 years old. However, there is another side to the story.

Discovery

The Coso Artifact was found by rock and geode hunters Mike Mikesell, Virginia Maxey, and Wallace Lane. On February 13, 1961, the trio was hunting for geodes to sell in their gift shop. They hunted in the area of Olancha, California and then brought their finds back to the shop to be sorted and cut. When one of the “geodes” was cut, a cylinder of metal and ceramic was found inside. One of the discoverers of the Coso said that an archaeologist dated the material to 500,000 years ago. It was also said that it might be hardened clay and that it also contained what looked like a nail and a washer.

Examination

The date of the Coso Artifact relies on the assumption that it is a geode. The only known thorough physical examination of the Coso Artifact found that the material was too soft to be a geode. It also lacked the telltale quartz crystals found in crystals. Some softer materials can form around a modern item relatively quickly, whereas a geode cannot. That renders the age estimate not necessarily incorrect but based on a faulty belief. The most telling part of the examination came with an x-ray of the item inside. It revealed that the metal was a cylinder with a screw-like item on one end and a flare on the other end.

For a period of time following the investigation, the Coso Artifact disappeared. The three individuals who found it no longer talked about it and one may have since passed away. Nonetheless, the first investigation and the photos (including x-ray photos) that resulted have made it possible for experts to make some interesting discoveries about the item.

The photos did not show a modern item inside of a geode. However, the item inside the geode was tentatively identified.

Mystery Solved: It’s a 1920s Champion Spark Plug

Pacific Northwest Skeptic Pierre Stromberg took an interest in this artifact and decided to look into it. Unable to use the Coso Artifact as a point of reference, he used photos and x-rays taken of the item decades earlier. The leading theory suggested it was a spark plug, as it displayed many of the same characteristics.

However, the screw-like end posed a problem. He contacted the Spark Plug Collectors of America, asking them to identify it, if possible. He received word back that the item had been positively identified as a 1920s Champion spark plug used in Ford Model T or Model A engines. There was no doubt in the man’s mind. Other spark plug collectors confirmed that the Coso Artifact is indeed a spark plug, just designed differently than the spark plugs we use today.

The logical explanation is that it is indeed a spark plug. The nail and washer discovered with the item somehow became encased in a harden clay over the years.

A Re-Evaluation Confirms an Honest Mistake

It seems unlikely that it was a hoax, given the hands-off approach that the discoverers have taken following the initial investigation.

In April 2018, the family of one of the founders allowed Stromberg to conduct another examination by a geologist at the University of Washington. The initial conclusion was correct. The item is a 1920s sparkplug encased in iron oxide.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

Strange stuff, gassey......thanks for the info.............

gassey likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

14 th February 1945

Bombing of Dresden :

World War II: On the first day of the bombing of Dresden, the British Royal Air Force and the United States Army Air Forces begin fire-bombing Dresden.

From February 14 to February 15, 1945, during the final months of World War II (1939-45), Allied forces bombed the historic city of Dresden, located in eastern Germany. The bombing was controversial because Dresden was neither important to German wartime production nor a major industrial center, and before the massive air raid of February 1945 it had not suffered a major Allied attack. By February 15, the city was a smoldering ruin and an unknown number of civilians—estimated between 22,700 to 25,000–were dead.

Bombing of Dresden: Background

By February 1945, the jaws of the Allied vise were closing shut on Nazi Germany. In the west, Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s (1889-1945) desperate counteroffensive against the Allies in Belgium’s Ardennes forest had ended in total failure. In the east, the Red army had captured East Prussia and reached the Oder River, less than 50 miles from Berlin. The once-proud Luftwaffe was a skeleton of an air fleet, and the Allies ruled the skies over Europe, dropping thousands of tons of bombs on Germany every day.

From February 4 to February 11, the “Big Three” Allied leaders–U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt (1882-1945), British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965) and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin (1878-1953)–met at Yalta in the USSR and compromised on their visions of the postwar world. Other than deciding on what German territory would be conquered by which power, little time was given to military considerations in the war against the Third Reich. However, Churchill and Roosevelt did promise Stalin to continue their bombing campaign against eastern Germany in preparation for the advancing Soviet forces.

World War II and Area Bombing

An important aspect of the Allied air war against Germany involved what is known as “area” or “saturation” bombing. In area bombing, all enemy industry–not just war munitions–is targeted, and civilian portions of cities are obliterated along with troop areas. Before the advent of the atomic bomb, cities were most effectively destroyed through the use of incendiary bombs that caused unnaturally fierce fires in the enemy cities. Such attacks, Allied command reasoned, would ravage the German economy, break the morale of the German people and force an early surrender.

Germany was the first to employ area bombing tactics during its assault on Poland in September 1939. In 1940, during the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe failed to bring Britain to its knees by targeting London and other heavily populated areas with area bombing attacks. Stung but unbowed, the Royal Air Force (RAF) avenged the bombings of London and Coventry in 1942 when it launched the first of many saturation bombing attacks against Germany. In 1944, Hitler named the world’s first long-range offensive missile V-1, after “vergeltung,” the German word for “vengeance” and an expression of his desire to repay Britain for its devastating bombardment of Germany.

The Allies never overtly admitted that they were engaged in saturation bombing; specific military targets were announced in relation to every attack. However, it was but a veneer, and few mourned the destruction of German cities that built the weapons and bred the soldiers that by 1945 had killed more than 10 million Allied soldiers and even more civilians. The firebombing of Dresden would prove the exception to this rule.

Bombing of Dresden: February 1945

Before World War II, Dresden was called “the Florence of the Elbe” and was regarded as one the world’s most beautiful cities for its architecture and museums. Although no German city remained isolated from Hitler’s war machine, Dresden’s contribution to the war effort was minimal compared with other German cities. In February 1945, refugees fleeing the Russian advance in the east took refuge there. As Hitler had thrown much of his surviving forces into a defense of Berlin in the north, city defenses were minimal, and the Russians would have had little trouble capturing Dresden. It seemed an unlikely target for a major Allied air attack.

On the night/morning of February 13 /14, hundreds of RAF bombers descended on Dresden in two waves, dropping their lethal cargo indiscriminately over the city. The city’s air defenses were so weak that only six Lancaster bombers were shot down. By the morning, some 800 British bombers had dropped more than 1,400 tons of high-explosive bombs and more than 1,100 tons of incendiaries on Dresden, creating a great firestorm that destroyed most of the city and killed numerous civilians. Later that day, as survivors made their way out of the smoldering city, more than 300 U.S. bombers began bombing Dresden’s railways, bridges and transportation facilities, killing thousands more. On February 15, another 200 U.S. bombers continued their assault on the city’s infrastructure. All told, the bombers of the U.S. Eighth Air Force dropped more than 950 tons of high-explosive bombs and more than 290 tons of incendiaries on Dresden. Later, the Eighth Air Force would drop 2,800 more tons of bombs on Dresden in three other attacks before the war’s end.

Bombing of Dresden: Aftermath

The Allies claimed that by bombing Dresden, they were disrupting important lines of communication that would have hindered the Soviet offensive. This may be true, but there is no disputing that the British incendiary attack on February 14 to was conducted also, if not primarily, for the purpose of terrorizing the German population and forcing an early surrender. It should be noted that Germany, unlike Japan later in the year, did not surrender until nearly the last possible moment, when its capital had fallen and Hitler was dead.

Because there were an unknown number of refugees in Dresden at the time of the Allied attack, it is impossible to know exactly how many civilians perished. After the war, investigators from various countries, and with varying political motives, calculated the number of civilians killed to be as little as 8,000 to more than 200,000. In 2010, the city of Dresden published a revised estimate of 22,700 to 25,000 dead.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

15 th February 1971

Decimal day :

The decimalisation of the currencies of the United Kingdom and Ireland is completed on Decimal Day.

For those who have only known British money after the overhaul of decimalisation in 1971, the old currency may seem a confusing array of arithmetic and colourfully named coins.

There were 12 pennies in a shilling and 20 shillings to the pound, but within that were farthings, halfpennies, thrupenny bits, tanners, half-crowns, crowns and florins. This system was in use for over a millennium and had its origins in Roman times, when a pound of silver would be divided into 240 denarii.

The idea of a decimal currency, based on units of 10 and 100, had been mooted long before Britain made the switch. Other nations did so much earlier: Russia made the transition in 1704, then France and the US in the 1790s. Yet it would not be until a number of Commonwealth nations made the change in the 1960s that momentum led Britain to join what the Evening Standard called “The Decimal Revolution”.

Chancellor of the Exchequer James Callaghan announced the decision on 1 March 1966 and the Decimal Currency Board (DCB) was created to make the transition, which would not take full effect for five years, as smooth as possible. Central to the campaign was a public information drive of posters, leaflets, BBC broadcasts, an instructional song by Max Bygraves and a 26-minute sitcom-style film for ITV called Granny Gets the Point.

To ease the change further, the new 5p and 10p coins were introduced in April 1968, then the 50p the following year. All coins had a portrait of the Queen on one side, while the reverse boasted the work of esteemed sculptor Christopher Ironside. He had started in 1962 on the instructions of a preempting Royal Mint, only for Callaghan to launch a public competition for the coin designs, causing Ironside to start again and work tirelessly in order to win the right to “get the tails”, as he put it.

Finally, the 1p, 2p and halfpenny went into circulation on Monday 15 February 1971 – Decimal Day, also referred to as D-Day.

The banks had closed for four days in preparation and shops had currency converters to display prices in both old and new money, but the DCB had done its job. Apart from some lamenting the loss of pounds, shillings and pence, everything went smoothly as two billion new coins filled the nation’s purses.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

16 th February 1923

King Tut :

Howard Carter unseals the burial chamber of Pharaoh Tutankhamun.

On 16th February 1923, Howard Carter and his team of archaeologists made a discovery that changed the world forever. Three months after unearthing a mysterious step, Carter’s team worked tirelessly to reveal the entrance to the mysterious tomb that lay just below the surface. Little did they know just how significant of a discovery it would turn out to be.

The tomb of Tutankhamun was remarkably well preserved, having remained untouched for over three millennia. Containing more than 5,000 individual artefacts and treasures, when Carter and his team crossed the threshold, they were the first to have done so in 3,200 years.

Dripping with gold and jewels, the boy king’s tomb was filled with everything from furniture to board games. The wide variety of items held within the vaults shared a glimpse of what royal life was like in ancient Egypt. As more and more items were removed and catalogued, it snared the imaginations of millions worldwide.

Thanks to the booming mainstream media, news of the discovery spread across the globe like wildfire, and it wasn’t long until it went viral. Egyptology became an overnight sensation and seeped into popular culture almost immediately. It’s no wonder that 100 years on, its impact is still hugely influential. Here are five ways that Howard Carter’s discovery changed the world's cultural landscape forever.

1. Art Deco

Art Deco was starting to blossom around the same time as Carter’s discovery, so it only makes sense that one of the most significant cultural events would influence the burgeoning art style.

Inspired by the opulent and detailed artwork painted onto the walls of Tutankhamun’s tomb, Art Deco started to incorporate the geometric shapes, motifs, and luxury seen in the king’s burial chambers.

Icons like palm trees, scarabs, and cats were a common occurrence in the Art Deco style, and the decadent use of rich gold as a decoration was heavily motivated by the luxury and grandeur inside the tomb.

2. Marketing

It didn’t take long for marketers to jump on board the hype train. Everything from lemons to cigarettes was rebranded to feature the words 'Egypt' or 'King Tut' in the hope of cashing in on the trend. Marketing posters and adverts featured iconic Egyptian scenery that evoked ideas of luxury and style.

Nothing was immune to the marketing power of Egyptomania. Perfume adverts featured women dressed in ancient Egyptian style robes drawn fanning themselves, while soap adverts featuring a sarcophagus boasted that they could re-incarnate beauty.

3. Fashion

It wasn’t just artwork and thrones that were removed from the tomb - there were fashion items too. Chests filled with clothing included everything like loincloths, shawls, sashes, gloves, headdresses, sandals, and animal skins. Within weeks, articles were popping up in newspapers around the world discussing how collections were dominated by Egypt.

While some designers drew inspiration for the cut and style of their clothing, others created intricately patterned fabrics inspired by the tomb’s artwork. Even the flapper style, perhaps the most iconic fashion trend of the early 1900s, was heavily influenced by its severely cut bobs and Egyptian-inspired headdresses.

4. Architecture

With the rise in skyscrapers starting in the 1920s and 1930s, many likened the new architectural advancement to a modern-day equivalent of the pyramids. Built at the height of King Tut fever, buildings like the Chrysler Building in New York and the Hoover Building in London are living examples of how the Ancient Egyptians' intricate artwork and repeating geometric patterns translated into modern architecture.

It wasn’t just the outsides of the buildings that were inspired, either. Rooms of gold and polished brass were designed to mimic the luxurious gold walls of the tombs, with every inch of the buildings decorated. Furniture mimicked the Ancient Egyptian style, while Art Deco artwork and flourishes tied the interior decorating together.

5. Beauty

Personal beauty products were quick to start marketing their items, like eyeliner and face powder in Egyptian-inspired packaging. Makeup and beauty trends sprung up from the myriad pictures of ancient Egyptian men and women featured in the tomb’s artwork.

Thick, heavy eyeliner trends (which still go in and out of fashion even now) mimicked the heavy kohl on Tutankhamun’s death mask, while the short bob hairstyle also rose from the artworks of the tomb. Even accessories, jewellery and headdresses were fashioned from pictures of the artwork.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

17 th February 1978

La Mon restaurant bombing :

The Troubles: The Provisional IRA detonates an incendiary bomb at the La Mon restaurant, near Belfast, killing 12 and seriously injuring 30 others, all Protestants.

The La Mon restaurant bombing was an incendiary bomb attack by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) on 17 February 1978 and has been described as one of the worst atrocities of the Troubles. It took place at the La Mon House hotel and restaurant, near Belfast.

The IRA left a large incendiary bomb, containing a napalm-like substance, outside one of the restaurant's windows. There were 450 diners, hotel staff and guests inside the building. The IRA said that they tried to send a warning from a public telephone, but were unable to do so until nine minutes before the bomb detonated. The blast created a fireball, killing 12 people and injuring 30 more, many of whom were severely burnt. Many of the injured were treated in the Ulster Hospital in nearby Dundonald.

A Belfast native, Robert Murphy, received twelve life sentences in 1981 for the manslaughter of those who were killed. Murphy was freed from prison on licence in 1995.

Bombing

Warnings

On 17 February 1978, an IRA unit planted an incendiary bomb attached to petrol-filled canisters on meat hooks outside the window of the Peacock Room in the restaurant of the La Mon House Hotel, located at Comber, County Down, about 6miles southeast of central Belfast. After planting the bomb, the IRA members tried to send a warning from the nearest public telephone, but found that it had been vandalised. On their way to another telephone, they were further delayed when forced to stop at an Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) checkpoint.

By the time they were able to send the warning, only nine minutes remained before the bomb exploded at 21:00. The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) base at Newtownards had received two further telephone warnings at 20:57 and 21:04. By the time the latter call came in, it was too late. When an officer telephoned the restaurant to issue the warning he was told "For God's sake, get out here – a bomb has exploded!" It has been stated that the IRA were targeting RUC officers they believed were meeting in the restaurant that night, but had got the wrong date and that the meeting of RUC officers had taken place exactly a week before.

Explosion and fireball

That evening the two main adjoining function rooms, the Peacock Room and Gransha Room, were packed with people of all ages attending dinner dances. Including the hotel guests and staff, there was a total of 450 people inside the building. The diners had just finished their first course when the bomb detonated, shattering the window outside of which it was attached and vaporising the canisters. The explosion created an instantaneous and devastating fireball of blazing petrol, 40feet high and 60feet wide, which engulfed the Peacock Room. Twelve people were killed, having been virtually burnt alive, and some 30 others were injured, many critically. Some of the wounded lost limbs, and most received severe burns. One badly burnt survivor described the inferno inside the restaurant as "like a scene from hell" whilst another said the blast was "like the sun had exploded in front of my eyes". There was further pandemonium after the lights went out and choking black smoke filled the room. The survivors, with their hair and clothing on fire, rushed to escape the burning room. It took firemen almost two hours to put out the blaze. The dead were all Protestant civilians. Half were young married couples. Most of the dead and injured were members of the Irish Collie Club and the Northern Ireland Junior Motor Cycle Club, holding their yearly dinner dances in the Peacock Room and Gransha Room, respectively. The former took the full force of the explosion and subsequent fire; many of those who died had been seated nearest the window where the bomb had gone off. Some of the injured were still receiving treatment 20 years later.

The device was a small blast bomb attached to four large petrol canisters, each filled with a home-made napalm-like substance of petrol and sugar. According to a published account by retired RUC Detective Superintendent Kevin Benedict Sheehy, this type of device had already been used by the IRA in more than one hundred attacks on commercial buildings before the La Mon attack. This was designed to stick to whatever it hit, a combination which caused severe burn injuries. The victims were found beneath a pile of hot ash and charred beyond recognition, making identity extremely difficult as their individual features had been completely burned away. Some of the bodies had shrunk so much in the intense heat, it was first believed that there were children among the victims. One doctor who saw the remains described them as being like "charred logs of wood".

Aftermath

The day after the explosion, the IRA admitted responsibility and apologised for the inadequate warning. The hotel had allegedly been targeted by the IRA as part of its firebomb campaign against commercial targets. Since the beginning of its campaign, it had carried out numerous such attacks with the stated goal of harming the economy and causing disruption, which it believed would put pressure on the British Government to withdraw from Northern Ireland. The resulting carnage brought quick condemnation from other Irish nationalists, with one popular newspaper comparing the attack to the 1971 McGurk's Bar bombing. Sinn Féin president Ruairí Ó Brádaigh also strongly criticised the operation. In consequence of the botched warning, the IRA Army Council gave strict instructions to all units not to bomb buses, trains or hotels.

As all the victims had been Protestant, many Protestants saw the bombing as a sectarian attack against their community. Some unionists called for the return of the death penalty, with one unionist politician calling for republican areas to be bombed by the Royal Air Force. The same day, about 2,000 people attended a lunchtime service organised by the Orange Order at Belfast City Hall. Belfast International Airport shut for an hour, while many workers in Belfast and Larne stopped work for a time. Workers at a number of factories said they were contributing a half-day's pay to a fund for the victims. Ulster loyalists criticised the then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Roy Mason, for his "complacent attitude" to the attack. He stated that the explosion was "an act of criminal irresponsibility" performed "by remnants of IRA gangs". He also stated that the IRA was on the decline.

A team of 100 RUC detectives was deployed in the investigation. As part of the investigation, 25 people were arrested in Belfast, including Gerry Adams. Adams was released from custody in July 1978. Two prosecutions followed. One Belfast man was charged with twelve murders but was acquitted. He was convicted of IRA membership but successfully appealed. In September 1981, another Belfast man, Robert Murphy, was given twelve life sentences for the manslaughter of those who died. Murphy was freed on licence in 1995. As part of their bid to catch the bombers, the RUC passed out leaflets which displayed a graphic photograph of a victim's charred remains.

In 2012, a news article quoting unnamed Republican sources stated that two members of the IRA bombing team, including the getaway driver, were double agents working for the Special Branch. According to the article, one of the agents was Denis Donaldson. That year, Northern Ireland's Historical Enquiries Team (HET) completed a report on the bombing. It revealed that important police documents, including interviews with IRA members, have been lost. A number of the victims' families criticised the report and called for a public inquiry. They stated the documents had been removed to protect certain IRA members. Unionist politician Jim Allister, who had been supporting the families, said: "There is a prevalent belief that someone involved was an agent and that is an issue around which we need clarity".

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

18 th February 1930

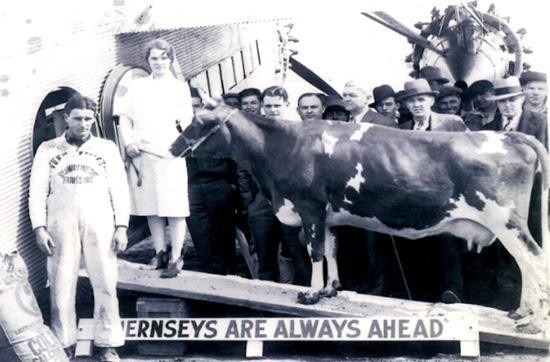

Elm Farm Ollie :

Elm Farm Ollie becomes the first cow to fly in a fixed-wing aircraft and also the first cow to be milked in an aircraft.

Elm Farm Ollie: The Story of the First Cow to Take Flight

flying cow

On February 18, 1930, the first cow to ever take flight ascended into the sky in a Ford Tri-Motor. As part of the celebration of the International Air Exposition in St. Louis, Elm Farm Ollie was flown from Bismarck, Missouri to St. Louis, a distance of 72 miles. Elm Farm Ollie was the first cow to take flight and the first cow to be milked on a plane.

Putting a cow on a plane was a publicity stunt, but also an opportunity for scientists to study the affect of high altitude on a cow being milked. Elm Farm Ollie was a Guernsey cow who could produce large quantities of milk. It was said that Elm Farm Ollie was milked three times a day and was selected for the flight because of her ability to give lots of milk. Guernsey cows are orange-red and white in color and are used in dairy farming. On her epic journey, Elm Farm Ollie produced 24 quarts of milk. The milk was then put into paper cartons and parachuted down to the spectators below. One of the famous people who is rumored to have drank Ollie’s milk is Charles Lindbergh. Elsworth W. Bunce was a lucky man from Wisconsin who had the honor of milking Ollie and earned the distinction as the first man to milk a cow mid-flight.

Weighing over 1000 pounds, loading Elm Farm Ollie onto the plane did not seem like an easy task. However, this cow was also selected for flight because of her docile and calm nature. Before the flight, Elm Farm Ollie was known as “Nellie Jay”. After making history she was given the moniker “Sky Queen”.

Ollie only lived to be about 10 years old, but her fame has lived on. Ollie is the subject of numerous stories, cartoons and poems written in her honor and she is the subject of a painting by E.D. Challenger. An excerpt from one song commemorating Ollie goes:

“Sing we praises of that moo cow,

Airborne once and ever more,

Kindness, courage, butter, cream cheese,

These fine things we can’t ignore.”

–From “The Bovine Cantata in B-Flat Major,”

by Giacomo Moocini and Ludwig Von Bovine

(Barry Levenson and the Mount Horeb Mustard Museum.)

Elm Farm Ollie day is celebrated every February 18 at the National Mustard Museum in Wisconsin.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly- PlatinumProudly made in Wigan platinum award

- Posts : 36745

Join date : 2019-07-17

Age : 53

gassey likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

19 th February 1985

Take heart :

William J. Schroeder becomes the first recipient of an artificial heart to leave the hospital.

First patient with implanted artificial heart, William J. Schroeder, departs from hospital

The quest to develop an artificial human heart must have seemed dazzlingly close in the 1950s, as doctors already knew pricesely the organ’s mechanics and function. A heart-and-lung machine was already proven successful in taking over the functions of both organs for a short while, during surgery. And a small-scale mechanical replica of a heart was developed, but never used, since it could not be built out of any material the body could accept. Still, those last few challenges on the way to a successful artificial human heart proved quite difficult to overcome, and it took three more decades until the procedure was perfected.

On this day, February 19, in 1985, the first patient with the model Jarvik-7 model of the artificial heart was released from the hospital.

The Jarvik-7 heart implanted in Schroeder was the pinnacle of technology at the time. Made from composite materials designed to grow into the surrounding blood vessels, and with air-powered ventricles operating much like a natural heart would, it was designed in every way to integrate into the body. Still, it could not have been easy for Schroeder: the Jarvik heart required an external operating system about the size of a refrigerator, which included the heart’s battery charger and beat speed regulator.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

20 th February 2003

The Station nightclub disaster:

During a Great White concert in West Warwick, Rhode Island, a pyrotechnics display sets the Station nightclub ablaze, killing 100 and injuring over 200 others.

A fire claimed 100 lives during a Great White show on Feb. 20, 2003 at the Station nightclub in West Warwick, R.I. More than 200 others were also injured in a blaze caused by the band's pyrotechnic display.

Road manager Daniel Biechele set off the pyrotechnics during the opening number, as planned. The sparks unexpectedly ignited the foam used for soundproofing the ceiling of the club. The flames spread quickly, engulfing the club, and claiming the lives of many of those trying to escape.

Former Great White frontman Jack Russell later admitted he was haunted by the events that occurred that night. "My heart aches for all the families and friends of the victims whose lives will forever be changed by this terrible tragedy," he was quoted as saying on the 10th anniversary of the tragedy. "I too lost many friends that night, but I can’t begin to equate that to the loss of a family member. For what it’s worth, you have been in my prayers and always will be.”

Russell performed a benefit concert on Feb. 7, 2013 in commemoration of the tragedy, with all proceeds going to the victims families. In a sign of the pain and acrimony that still remained, however, the Station Fire Memorial Foundation refused to accept any money from Russell: "We feel the upset caused by his involvement would outweigh the amount of funds received."

Many of the surviving victims and the families of those killed felt Russell had not done enough to apologize or atone for his part in the tragedy. "Everyone would look at this differently if Jack Russell would stand up and say, ‘I’m sorry,'" Gina Russo, a concertgoer who was burned in the fire, explained to the Boston Globe.

Great White's Jack Russell Discusses the Station Nightclub Fire

When asked if he felt horrible about the tragedy in a 2013 interview with Rover Radio, Russell answered, "Of course I do." He went on to explain his reluctance to discuss the matter further: "I've said everything that I ever want to say about it, I've done a million interviews. ... Every time I say something, I hurt somebody ... I just prefer not to talk about it. It was a horrible thing that happened."

The brothers who owned the nightclub, Jeff and Michael Derderian, were found guilty of one hundred counts of involuntary manslaughter, and have used varying charitable methods to atone for the disaster. Representing the families of the deceased, lawyer John Barylick negotiated a $176 million civil settlement from, as he put it, "the persons and corporations responsible for the fire."

Biechele pled guilty to involuntary manslaughter and was sentenced to four years in prison for his role in the tragedy. He sent a handwritten letter of apology to each of the families affected by the fire. Partially in return for this openness and admission of responsibility, many of those same families publicly supported his early parole, which was granted about halfway through his sentence.

In 2021, the Derderians gave an interview to 48 Hours, explaining, for the first time, their side of what happened. In that conversation, they claimed that Great White's contract did not mention the use of pyrotechnics, that the fire marshal had not performed the venue's required tests and that the company who supplied the nightclub with what was supposed to be noise-cancelling foam, had accidentally sent them highly-flammable packing foam instead.While the accuracy of these claims was debated by other parties, there's no doubt a multitude of factors contributed to the tragedy.

In 2017, Station Fire Memorial Park was opened on the site where the nightclub once stood. Throughout the park, each of the fire's victims are honored by name, while tributes also thank the first responders for their life-saving efforts that night.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

21 st February 1952

Identity cards:

1952 – The British government, under Winston Churchill, abolishes identity cards in the UK to "set the people free".

National Identity Cards were introduced by the National Registration Act at the beginning of World War 2…. Every man, woman and child was issued with one and on it was recorded name, age, sex, address, marital status and occupation…. The first cards were brown – with the introduction of blue cards for adults in 1943 and green cards with a photograph were issued to government officials….

At the end of the War the Labour Government, under Clement Attlee, opted to keep the identity card – which was not a popular decision amongst much of the population…. Labour argued that the card was important for preventing fraud, for rationing, the health service and benefits such as family allowance….

In their election manifesto the Conservative Party had pledged to scrap the cards…. It was in answer to a question that he had been asked in the Commons that Health Minister Harry Crookshank said… “It is no longer necessary to require the public to possess and produce an identity card, or to notify change of address for National Registration purposes, though the numbers will continue to be used in connection with the National Health Service”… His reply was met with cheers from members in the House of Commons….

From then on other forms of identification were acceptable when required, such as passport, driving licence, trade union membership card etc…. However, the National Registration number was kept and became the National Health Service number….

In 2006 the Labour Government made the Identity Cards Act law…. A voluntary National Identity Card scheme with a National Identity Register database…. It proved to be very controversial and when the Conservatives came to power the Act was repealed in 2010….

An adult identity card.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

22 nd February 2006

The Securitas depot robbery :

At least six men stage Britain's biggest robbery, stealing £53m (about $92.5 million or €78 million) from a Securitas depot in Tonbridge, Kent.

The 2006 Securitas depot robbery in Tonbridge, England, was the UK's largest cash heist. It began with a kidnapping on the evening of 21 February 2006 and ended in the early hours of 22 February, when seven criminals stole almost £53 million. The gang left behind another £154 million because they did not have the means to transport it.

After doing surveillance and placing an insider at the Securitas depot, the gang abducted the manager and his family. The same night, they tricked their way inside the building, and tied up 14 workers at gunpoint. The criminals stole £52,996,760 in used and unused sterling banknotes. Most of the getaway vehicles were found in the following week, one containing £1.3 million in stolen notes. In raids by Kent Police, £9 million was recovered in Welling and £8 million in Southborough. By 2007, 36 people had been arrested in relation to the crime.

At trial at the Old Bailey in London in 2007, five people were convicted, and received long sentences, including the inside man, Emir Hysenaj. A woman who had made prosthetic disguises for the gang gave evidence in return for the charges against her being dropped. Lee Murray, the alleged mastermind, had fled to Morocco with his friend and accomplice Paul Allen. He successfully fought extradition to the UK and was imprisoned there for the robbery. Allen was extradited and after a second trial in 2008 was jailed in the UK; upon his release he was shot and injured in 2019. By 2016, £32 million remained unrecovered, and several suspects were still at large.

Robbery

In the early evening of Tuesday, 21 February 2006, Dixon, the depot manager was driving home along the A249 when he was pulled over just outside Stockbury, a village northeast of Maidstone, by what he presumed was an unmarked police car. The Volvo S60 had flashing blue lights in its grille and one of the two uniformed officers came to Dixon's window, asking him to turn off his engine and leave the keys in the ignition. Breaching protocol, Dixon followed the officer's order to step out of his car and to sit in the other car, where he was handcuffed. His car was moved off the road and the Volvo travelled west on the M20 motorway to the West Malling bypass. The criminals play-acted driving him to a police station before revealing their deception and threatening him with a gun at Mereworth. He was tied up and transferred into a white van which drove to Elderden Farm near Staplehurst.

The two men impersonating police officers next drove to Dixon's home in Herne Bay and spoke to Lynn Dixon, telling her that her husband had crashed his car and that she and her son should accompany them to the hospital as quickly as possible. When she got into the car Lynn Dixon realised it was not a real police car and the men told her she was being abducted; they took her to the farm as well. Colin Dixon was then interrogated about the layout of the depot and warned at gunpoint that the lives of his family members depended upon his actions.

Around 01:00 on Wednesday, 22 February 2006, three vehicles headed to the depot. Lynn Dixon and her son were held in the back of a 7.5 tonne white Renault Midlum lorry; Colin Dixon and the other gang members travelled in a Vauxhall Vectra and the Volvo. The vehicles split up, and the Volvo arrived at the depot at 01:21. Dixon and a gang member dressed as a police officer got out of the car and walked towards the pedestrian entrance. Dixon rang the bell and looked through the window at the control room operator. Instead of querying why Dixon was returning at night or why he was with an officer, the inexperienced operator opened the door and let the two men through the airlock into the building. The entire robbery was filmed on the building's CCTV and when Kent Police later reviewed the footage, they nicknamed this gang member "Policeman". "Policeman" subdued the operator and, without being asked, Dixon pressed the button which opened the gate and allowed the vehicles to enter the yard.

The rest of the gang now entered the building. One man was later nicknamed "Stopwatch", because he was wearing a stopwatch to time the robbery in an echo of the film Ocean's Eleven. Others were called "Shorty", "Hoodie" and "Mr Average". The criminals' faces were hidden by balaclavas and they were armed with handguns, shotguns, AK-47 assault rifles and a Škorpion submachine gun. Dixon urged staff to comply with the gang's commands, and 14 workers were tied up. Nobody pressed an alarm. The seven members of the gang attempted to load metal cages full of banknotes into the lorry and found they were too heavy, so one criminal tried to drive the Lansing Linde power lifter and the rest shoved the hostages out of the way. It was difficult to manoeuvre the lifter and a Securitas worker was ordered to drive it; when he kept deliberately crashing it, Dixon was told to use a pallet mover. The worker then wedged the power lifter between the tail lift of the truck and the loading bay, rendering it useless. When Dixon pumped the pallet mover up, "Hoodie" became suspicious and pointed a gun at his head; frustrated by the slow progress, the other gang members grabbed bundles of money in their hands and filled up shopping trolleys. The criminals stole £52,996,760 in used and unused banknotes; another £154 million would not fit in the lorry and they had to leave it behind. In total they took seventeen cages and three trolleys full of banknotes.

The staff workers were left locked up inside empty cages, as were Lynn Dixon and her son. No alarm had been set off and the gang ordered the staff to stay still when they left at 02:44. At 03:15, when they were sure the robbers had gone, the staff triggered an alarm which called the police. The police arrived and began the investigation by interviewing the staff and taking their clothes and their DNA profiles.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

23 rd February 1820

Cato street conspiracy :

Cato Street Conspiracy: A plot to murder all the British cabinet ministers is exposed and the conspirators arrested.

In the early evening of 23 February 1820, some twenty men assembled in a small hayloft above a stable in Cato Street, off the Edgware Road in London. They were led by Arthur Thistlewood, a well-known militant follower of the radical doctrines of Thomas Spence; the majority of the other men were destitute tradesmen from England, Scotland and Ireland. Joining their ranks was the Jamaican-born William Davidson. The hayloft had been converted into the ramshackle headquarters of a revolutionary conspiracy to assassinate the British Cabinet, who were believed to be dining in nearby Grosvenor Square.

The conspirators were driven by a thirst for vengeance for the ‘Peterloo massacre’ the previous summer, when a peaceful political rally calling for parliamentary reform was charged by the Manchester Yeomanry, killing eighteen and injuring over 700 people. Thistlewood was also enthused by the brutal assassination of Charles Ferdinard, the heir to the French throne, in Paris, ten days before the fated gathering in Cato Street. Ferdinard was stabbed on leaving an opera house in Paris by Louis Pierre Louvel, a fanatical Bonapartist who craved nothing less than the eradication of the Bourbon monarchy. Thistlewood was newly invigorated on hearing of Louvel’s deed, believing that the time had come to strike against aristocratic and monarchical rule in Britain.

The Cato Street conspirators conceived an even more audacious action than the assassination of Ferdinard. After gathering at Cato Street to collect weapons (mostly pikes, swords and homemade guns), the revolutionary band intended to walk the short distance to the home of Lord Harrowby, the President of the Privy Council, the host for the Cabinet’s dinner. It was to be the ministers’ final meal: the conspirators planned to kill everyone in the dining room who held a position in government, with decapitation reserved for the two most loathed ministers, the Home Secretary, Viscount Sidmouth, and the Foreign Secretary, Lord Castlereagh. Their heads were to be mounted on spikes and paraded ghoulishly in public as befitted traitors to the ‘People’.

Following the tyrannicide, the revolutionaries planned to seize symbolic buildings and establish a provisional government. On hearing the news of the death of the Cabinet and reading the declaration of the new government that promised a new dispensation based on the emancipation of the people, they believed that radicals in the capital would join the conspirators en masse, which in turn would trigger a national rising. Eighteen-twenty was to be the year of the British Republic.

The conspirators were, however, betrayed. There was no dinner for the Cabinet in Grosvenor Square that night; unbeknown to Thistlewood and his followers, they had been set up by an agent provocateur, George Edwards, who had infiltrated the conspiracy. The hated Lord Sidmouth authorised the publication of the false notice of the Cabinet dinner to lure out the conspiracy from the shadows.

As the conspirators prepared for their mission, the Bow Street Runners (an ancestor of the Metropolitan Police) charged into the stable on Cato Street. The scene was chaotic, as the Runners frantically climbed up a ladder to the hayloft. The candles were extinguished by the conspirators as they attempted to escape; as fighting broke out in the darkness, Thistlewood fatally stabbed an officer. With the assistance of army troops, the revolutionaries were eventually rounded up and arrested. The Cato Street conspiracy was over.

Justice was swiftly dealt out to the ring leaders. Eleven men were tried at the Old Bailey in April: five were exiled to Australia for life; one served a prison sentence; and five, including Thistlewood, were hanged on 1 May. The hangman held up their severed heads to the gathered crowd, denouncing the condemned men as traitors to the Crown.

The legacy of the Cato Street conspiracy is a mixed one. Most radicals denounced the conspiracy and its aims once the plot became public. With the passing of the generations, Thistlewood and his band of revolutionaries were not claimed by any radical tradition, in the same way that nineteenth- and twentieth-century Irish republicans venerated past figures associated with violent struggle, such as Theobald Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet. Given the absence of a coherent revolutionary tradition in modern Britain (as opposed to Ireland), the Cato Street conspiracy does not quite ‘fit’ into a neatly defined historical narrative that emphasises peaceful and constitutional radical political reform.

It is, perhaps, for this reason that the significance of the plot is overlooked in (or even entirely missing from) many accounts of the early decades of nineteenth-century Britain. While the plot can be (and often is) dismissed as an act of lunacy, such a perspective overlooks the depth of hostility among radicals towards the government in the years immediately following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, especially in the aftermath of Peterloo. The refusal to treat the conspiracy seriously also means that historians can easily miss the international revolutionary networks that surrounded the ringleaders. The men who gathered in the hayloft on Cato Street in February 1820 did not trigger an insurrection against Britain’s aristocratic masters, but this was not necessarily a certainty, especially in the context of spiralling revolutionary fervour in Europe.

Cato street conspiracy :

Cato Street Conspiracy: A plot to murder all the British cabinet ministers is exposed and the conspirators arrested.

In the early evening of 23 February 1820, some twenty men assembled in a small hayloft above a stable in Cato Street, off the Edgware Road in London. They were led by Arthur Thistlewood, a well-known militant follower of the radical doctrines of Thomas Spence; the majority of the other men were destitute tradesmen from England, Scotland and Ireland. Joining their ranks was the Jamaican-born William Davidson. The hayloft had been converted into the ramshackle headquarters of a revolutionary conspiracy to assassinate the British Cabinet, who were believed to be dining in nearby Grosvenor Square.

The conspirators were driven by a thirst for vengeance for the ‘Peterloo massacre’ the previous summer, when a peaceful political rally calling for parliamentary reform was charged by the Manchester Yeomanry, killing eighteen and injuring over 700 people. Thistlewood was also enthused by the brutal assassination of Charles Ferdinard, the heir to the French throne, in Paris, ten days before the fated gathering in Cato Street. Ferdinard was stabbed on leaving an opera house in Paris by Louis Pierre Louvel, a fanatical Bonapartist who craved nothing less than the eradication of the Bourbon monarchy. Thistlewood was newly invigorated on hearing of Louvel’s deed, believing that the time had come to strike against aristocratic and monarchical rule in Britain.

The Cato Street conspirators conceived an even more audacious action than the assassination of Ferdinard. After gathering at Cato Street to collect weapons (mostly pikes, swords and homemade guns), the revolutionary band intended to walk the short distance to the home of Lord Harrowby, the President of the Privy Council, the host for the Cabinet’s dinner. It was to be the ministers’ final meal: the conspirators planned to kill everyone in the dining room who held a position in government, with decapitation reserved for the two most loathed ministers, the Home Secretary, Viscount Sidmouth, and the Foreign Secretary, Lord Castlereagh. Their heads were to be mounted on spikes and paraded ghoulishly in public as befitted traitors to the ‘People’.

Following the tyrannicide, the revolutionaries planned to seize symbolic buildings and establish a provisional government. On hearing the news of the death of the Cabinet and reading the declaration of the new government that promised a new dispensation based on the emancipation of the people, they believed that radicals in the capital would join the conspirators en masse, which in turn would trigger a national rising. Eighteen-twenty was to be the year of the British Republic.

The conspirators were, however, betrayed. There was no dinner for the Cabinet in Grosvenor Square that night; unbeknown to Thistlewood and his followers, they had been set up by an agent provocateur, George Edwards, who had infiltrated the conspiracy. The hated Lord Sidmouth authorised the publication of the false notice of the Cabinet dinner to lure out the conspiracy from the shadows.

As the conspirators prepared for their mission, the Bow Street Runners (an ancestor of the Metropolitan Police) charged into the stable on Cato Street. The scene was chaotic, as the Runners frantically climbed up a ladder to the hayloft. The candles were extinguished by the conspirators as they attempted to escape; as fighting broke out in the darkness, Thistlewood fatally stabbed an officer. With the assistance of army troops, the revolutionaries were eventually rounded up and arrested. The Cato Street conspiracy was over.

Justice was swiftly dealt out to the ring leaders. Eleven men were tried at the Old Bailey in April: five were exiled to Australia for life; one served a prison sentence; and five, including Thistlewood, were hanged on 1 May. The hangman held up their severed heads to the gathered crowd, denouncing the condemned men as traitors to the Crown.

The legacy of the Cato Street conspiracy is a mixed one. Most radicals denounced the conspiracy and its aims once the plot became public. With the passing of the generations, Thistlewood and his band of revolutionaries were not claimed by any radical tradition, in the same way that nineteenth- and twentieth-century Irish republicans venerated past figures associated with violent struggle, such as Theobald Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet. Given the absence of a coherent revolutionary tradition in modern Britain (as opposed to Ireland), the Cato Street conspiracy does not quite ‘fit’ into a neatly defined historical narrative that emphasises peaceful and constitutional radical political reform.

It is, perhaps, for this reason that the significance of the plot is overlooked in (or even entirely missing from) many accounts of the early decades of nineteenth-century Britain. While the plot can be (and often is) dismissed as an act of lunacy, such a perspective overlooks the depth of hostility among radicals towards the government in the years immediately following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, especially in the aftermath of Peterloo. The refusal to treat the conspiracy seriously also means that historians can easily miss the international revolutionary networks that surrounded the ringleaders. The men who gathered in the hayloft on Cato Street in February 1820 did not trigger an insurrection against Britain’s aristocratic masters, but this was not necessarily a certainty, especially in the context of spiralling revolutionary fervour in Europe.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

24 th February 1303

The battle of Roslin :

The English are defeated at the Battle of Roslin, in the First War of Scottish Independence.

Roslin 1303: Scotland's forgotten battle.

ON THIS DAY in 1303, a Scots army defied all the odds to defeat the English at the battle of Roslin. It ended as the bloodiest battle ever fought on British soil, but remains largely forgotten.

The Midlothian village of Roslin has one very obvious claim to fame with its chapel and the links to Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code. Tourists also visit the ruins of nearby Roslin Castle in large numbers every year. But the area bears an even greater historical distinction.

Precisely 720 years ago today, Roslin witnessed a Scots force of 8,000 clash with an English army almost four times its size, and, astonishingly, the Scots emerged victorious. It is estimated that 35,000 men lost their lives, which, if accurate, would make Roslin the bloodiest battle ever fought on British soil. Despite the huge death toll, the battle appears to have faded into obscurity and is often omitted from school textbooks.

“There are important parts of Scottish history which have been completely ignored or have been treated as irrelevant,” says Scots history expert and political activist, James Scott, “The Scots were led by Sir John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, and Simon Fraser. They had caught wind of the English advance and took on their forces one by one. They were split into three divisions, but the Scots were victorious on each occasion.”

Background

In the aftermath of the Battle of Falkirk in 1298, Scotland was occupied by the English under the governance of Sir John de Segrave, a knight of Edward I.

Sir John had fallen in love with Lady Margaret Ramsey of Dalhousie. But when he discovered that she had run off to marry Henry St Clair, Lord of Rosslyn, de Segrave was furious. He responded by obtaining permission from Edward I to organise an invasion to eliminate St Clair, on the basis that the marriage with Lady Margaret would further cement ties between Scotland and France.

Sir John de Segrave’s forces arrived in the Scottish Borders in mid-February, and from here the Scots began to track their advance north. De Segrave split his 30,000-strong army into three divisions, sending one group to attack Borthwick Castle near Gorebridge, the second group towards Lady Margaret’s Dalhousie Castle, and the third, led by Sir John himself, to Henry St Clair at Roslin. It is worth mentioning that Roslin at this time was a small hamlet surrounded by woods and open fields. No castle had been built and there wouldn’t be a chapel on the site for another 150 years.

The battle

On the eve of the battle John Comyn’s Scots army set up camp in the woods at Bilston to prepare themselves for attack.

The men launched their surprise offence under the cover of darkness the next morning and met with de Segrave’s forces as they slept by the River Esk. It was a slaughter. The English who fled were picked off by smaller groups of Scots positioned around the local area.

Comyn’s troops then laid siege to de Segrave’s second army holed up at Dalhousie Castle. Sir Ralph de Confrey, leader of the second division ordered his men to march towards the summit of Langhill to meet the Scots, but his forces were decimated by Comyn’s archers and pikemen. Again, the Scots spared no one.

Looking west towards the Pentland Hills, the Scots were roused by the sight of a huge canvas Saltire cross gleaming in the evening sun. It had been laid by a group of Cistercian monks under the order of Prior Abernethy in a bid to spur the exhausted Scottish forces on for their final test with the third English division at Mountmarle above the Esk Valley.

As they charged from Borthwick Castle, the English, led by Sir Richard Neville, were ambushed and crushed by hordes of Scots located on the higher ground of the valley. The long battle was finally won. It is thought that fewer than 2,000 English out of 30,000 survived. The Scots’ knowledge and use of the Roslin terrain had proved crucial in delivering a decisive, but wholly-unexpected victory. Defeated and heartbroken, de Segrave was captured and thrown in a dungeon with a hefty ransom on his head. Lady Margaret’s new husband Sir Henry St Clair would later go on to sign the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath.

Quite a tale. Why, then, have so few people in Scotland heard of the battle?

A bitter feud had existed between Sir John Comyn and Robert the Bruce for a number of years. Things came to a head in 1306 when, after a quarrel at Greyfriars Church in Dumfries, Bruce stabbed Comyn to death. It is therefore very possible that Bruce played a part in starving his rival of his rightful place in history, though this obviously doesn’t explain why the event continues to be so universally-ignored 700 years later - even by Roslin locals.

“It’s an incredible story,” says Edinburgh photographer and history aficionado, Tom Duffin, “I usually like to add a bit of background to my landscape photos for my Facebook followers, so when I researched Roslin after a shoot there I was blown away by how little I knew about the battle... Namely nothing at all.

“Considering it is arguably the most epic story of any battle between Scotland and the Auld Enemy, its obscurity is really quite astonishing. If you were to sit down and write it as a film script: ‘Haughty, posh Englishman rejected by flame-haired Scottish beauty, takes revenge by persuading the English king to lend his army to seek revenge on her new boyfriend, then gets bum kicked by a Scottish rabble to the resounding cheers and home-made banners of the local monks’... Well, frankly, you’ld be laughed at.

“They’d tell you to go back and re-write it with a more believable storyline.”

The battle of Roslin :

The English are defeated at the Battle of Roslin, in the First War of Scottish Independence.

Roslin 1303: Scotland's forgotten battle.

ON THIS DAY in 1303, a Scots army defied all the odds to defeat the English at the battle of Roslin. It ended as the bloodiest battle ever fought on British soil, but remains largely forgotten.

The Midlothian village of Roslin has one very obvious claim to fame with its chapel and the links to Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code. Tourists also visit the ruins of nearby Roslin Castle in large numbers every year. But the area bears an even greater historical distinction.

Precisely 720 years ago today, Roslin witnessed a Scots force of 8,000 clash with an English army almost four times its size, and, astonishingly, the Scots emerged victorious. It is estimated that 35,000 men lost their lives, which, if accurate, would make Roslin the bloodiest battle ever fought on British soil. Despite the huge death toll, the battle appears to have faded into obscurity and is often omitted from school textbooks.

“There are important parts of Scottish history which have been completely ignored or have been treated as irrelevant,” says Scots history expert and political activist, James Scott, “The Scots were led by Sir John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, and Simon Fraser. They had caught wind of the English advance and took on their forces one by one. They were split into three divisions, but the Scots were victorious on each occasion.”

Background

In the aftermath of the Battle of Falkirk in 1298, Scotland was occupied by the English under the governance of Sir John de Segrave, a knight of Edward I.

Sir John had fallen in love with Lady Margaret Ramsey of Dalhousie. But when he discovered that she had run off to marry Henry St Clair, Lord of Rosslyn, de Segrave was furious. He responded by obtaining permission from Edward I to organise an invasion to eliminate St Clair, on the basis that the marriage with Lady Margaret would further cement ties between Scotland and France.

Sir John de Segrave’s forces arrived in the Scottish Borders in mid-February, and from here the Scots began to track their advance north. De Segrave split his 30,000-strong army into three divisions, sending one group to attack Borthwick Castle near Gorebridge, the second group towards Lady Margaret’s Dalhousie Castle, and the third, led by Sir John himself, to Henry St Clair at Roslin. It is worth mentioning that Roslin at this time was a small hamlet surrounded by woods and open fields. No castle had been built and there wouldn’t be a chapel on the site for another 150 years.

The battle

On the eve of the battle John Comyn’s Scots army set up camp in the woods at Bilston to prepare themselves for attack.

The men launched their surprise offence under the cover of darkness the next morning and met with de Segrave’s forces as they slept by the River Esk. It was a slaughter. The English who fled were picked off by smaller groups of Scots positioned around the local area.

Comyn’s troops then laid siege to de Segrave’s second army holed up at Dalhousie Castle. Sir Ralph de Confrey, leader of the second division ordered his men to march towards the summit of Langhill to meet the Scots, but his forces were decimated by Comyn’s archers and pikemen. Again, the Scots spared no one.

Looking west towards the Pentland Hills, the Scots were roused by the sight of a huge canvas Saltire cross gleaming in the evening sun. It had been laid by a group of Cistercian monks under the order of Prior Abernethy in a bid to spur the exhausted Scottish forces on for their final test with the third English division at Mountmarle above the Esk Valley.

As they charged from Borthwick Castle, the English, led by Sir Richard Neville, were ambushed and crushed by hordes of Scots located on the higher ground of the valley. The long battle was finally won. It is thought that fewer than 2,000 English out of 30,000 survived. The Scots’ knowledge and use of the Roslin terrain had proved crucial in delivering a decisive, but wholly-unexpected victory. Defeated and heartbroken, de Segrave was captured and thrown in a dungeon with a hefty ransom on his head. Lady Margaret’s new husband Sir Henry St Clair would later go on to sign the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath.

Quite a tale. Why, then, have so few people in Scotland heard of the battle?

A bitter feud had existed between Sir John Comyn and Robert the Bruce for a number of years. Things came to a head in 1306 when, after a quarrel at Greyfriars Church in Dumfries, Bruce stabbed Comyn to death. It is therefore very possible that Bruce played a part in starving his rival of his rightful place in history, though this obviously doesn’t explain why the event continues to be so universally-ignored 700 years later - even by Roslin locals.

“It’s an incredible story,” says Edinburgh photographer and history aficionado, Tom Duffin, “I usually like to add a bit of background to my landscape photos for my Facebook followers, so when I researched Roslin after a shoot there I was blown away by how little I knew about the battle... Namely nothing at all.

“Considering it is arguably the most epic story of any battle between Scotland and the Auld Enemy, its obscurity is really quite astonishing. If you were to sit down and write it as a film script: ‘Haughty, posh Englishman rejected by flame-haired Scottish beauty, takes revenge by persuading the English king to lend his army to seek revenge on her new boyfriend, then gets bum kicked by a Scottish rabble to the resounding cheers and home-made banners of the local monks’... Well, frankly, you’ld be laughed at.

“They’d tell you to go back and re-write it with a more believable storyline.”

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

25 th February 1939

Anderson shelters :

As part of British air raid precautions, the first of two and a half million Anderson shelters is constructed in a garden in Islington, north London

ww2dbaseIn the years leading up to the war the British Government was increasingly concerned about how the public should be protected from air raids. In 1938, J. B. S. Haldane published a book called simply ARP in which he proposed that miles of brick lined tunnels be sunk into the London clay with multiple entrances and a complex system of ventilation. Haldane's suggestion was, however, rejected as being too costly, requiring too long to build and likely to create a shelter mentality through inactivity that might affect the normal functioning of the nation.

In Apr 1939 a government White Paper was published based on the recommendations of the Hailey Conference – an independent commission of experts - which rejected deep shelters in favour of dispersal and household protection with people spread out either in their own homes, in garden shelters or in small localised shelters. The White Paper endorsed the use of a corrugated steel garden shelter covered in earth. It was known as the Anderson shelter – though not, as is commonly thought, named after Sir John Anderson, 1st Viscount Waverley, the Lord Privy Seal and soon to be Neville Chamberlain's Home Secretary but for one of the designers, Dr. David Anderson.

On 25 Feb 1939 the first of two and a half million Anderson shelters began to be issued to households in vulnerable areas. The first went up in Islington in north London, but soon the shelters were springing up all over the country. Anyone earning less than £250 per year received a free shelter. Those with a higher income were charged £7 for their shelter. For people with no outdoor space, materials could be provided to strengthen a "refuge room". And for anyone not at home, or without outdoor space or "refuge room", communal street shelters with brick wall and concrete roofs would be offered. These feeble brick "Surface shelters" were not fondly remembered being notoriously used by prostitutes and people needing to relieve themselves. Nor were they particularly well built leading to a number of reported collapses during raids.

The Anderson shelter, designed by William Patterson and Oscar Carl Kerrison and built by John Summers and Sons of Shotton, were primarily designed to shelter up to six people from shrapnel and flying debris if not necessarily from a direct hit by a bomb. The 6 feet tall constructions were made of 14 curved and straight galvanised corrugated steel panels bolted together at the top with tapered rear and front walls, one with a door. The shelters often included a drainage sump in the floor to collect any rainwater that might sink in and the whole thing was buried 4ft into the ground with the roof covered with soil and turf. They were big enough for six people to fit into, though at a squeeze. The Andersons's chief problem was a lack of basic comfort. It was small, cold and dark and difficult for a family of four to six to bear over long winter nights. A lot of the shelters became waterlogged too. Nor did they cut out the frightening sounds of the bombing. Every member of the household was instructed to head to the shelter as soon as they heard the haunting air raid sirens, but with no lighting, heating or toilet facilities. It was not surprising that, as the Blitz wore on, many people started to desert their Andersons for the relative comfort of the house.

Many people who depended on Anderson shelters tried to make them look more appealing by decorating the outside with flower beds and plants. Actress Ann Todd, whose husband Nigel was a Spitfire pilot in the RAF, account of sheltering in an Anderson was typical of any people's experiences during the Blitz. With her young son she took advantage of the extra space to put in a few cushions, a table and toys for her son. But, despite her attempts at airing the shelter it still smelt of damp. Some communities even held competitions for the best looking plot. The sunken, corrugated huts even proved useful after the war with many owners opting to keep them in their gardens to house everything from chickens to garden tools. However, the large amount of time spent during the war in air raid shelters did come at a price with some children having to undergo sun-lamp treatment afterwards to deal with problems caused by the lack of sunlight and fresh fruit.

A lady waters vegatables on top of her backyard Anderson shelter in her south London home.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

26 th February 1960

Alitalia/Shannon air disaster :

A New York-bound Alitalia airliner crashes into a cemetery in Shannon, Ireland, shortly after takeoff, killing 34 of the 52 persons on board.

Italian airline Alitalia flight AZ618 4-engine propellor Douglas DC-7C was on route from Rome to New York and had stopped at Shannon for an unscheduled refuelling stop…. Shannon International Airport, in County Clare between Ennis and Limerick, was at the time a major refuelling stop for transatlantic flights….

After a brief stop of 45 minutes or so the aircraft took off to continue its journey at 1.34am, on a cold but clear Friday morning…. There had been no contact from the ‘plane and it seemed all was well – but about a mile from the airport the DC-7 crashed…. It struck the old graveyard situated beside the ruins of the 10th century Clanloghan Parish Church…. Its port wing-tip hit the wall of the cemetery, damaging some of the headstones on the south eastern side…. Some of the traditional family graves would still have been in use…. The aircraft then ploughed on, ending up in a nearby field before exploding and disintegrating…. After its refuelling stop the DC-7 was laden with some 7,000 gallons of fuel….the explosion was heard 17 miles away….

Thankfully the ‘plane was not full but out of the 52 onboard 11 of the 12 crew and 23 of the 40 passengers were killed….the other 18 were seriously injured…. The surviving cabin crew member had been seated at the rear of the aircraft…. Wreckage was scattered over a large area – bodies were found up to a mile away….

The aircraft had failed to gain enough height to clear the hill top…. At the official crash investigation no clear treason could be found as to the cause…. It could only be assumed that the DC-7, which had made its maiden flight in 1958, had rapidly lost height whilst making a steep turn to the left….

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

27 th February 1916

SS Maloja:

Ocean liner SS Maloja strikes a mine near Dover and sinks with the loss of 155 lives.

The Fate of P&O SS Maloja and the SS Empress of Fort William [+1916]

On the 27th February 1916 the Maloja left Tilbury en-route to Bombay with passengers and general cargo. As she approached the Strait of Dover at full speed and overtook the Canadian collier, Empress of Fort William. The Maloja was about 2 nautical miles off Dover when her starboard quarter struck one of the mines laid by U-Boat SM UC-6. There was a large explosion and the bulkheads of the second saloon were blown in. The liner started to sink at once and her captain, Commodore CE Irving (RNR) ordered the engines stopped and reversed to take her way off and the allow the lifeboats to be launched. Once in reverse, the engines could not be stopped and she was still going astern nearly half an hour later, when she sank with her props still spinning. Some 155 passengers and crew lost their lives. One of the largest wrecks in Kent waters, the Maloja today is largely covered with sand at some 21m, though some parts still stand proud at 5m. Divers report that this area of sand waves change landscape on a yearly basis and sometimes, dive to dive.

The Maloja was still in sight of the Empress of Fort William, which immediately went full ahead to assist. Hearing the mine explode on the Maloja and seeing the liner well down by the stern, her captain WD Shepherd ordered full speed and told his crew to prepare the boats. While still one nautical mile astern of the Maloja, the collier ran into the same minefield of UC-6, struck one of them and also began to sink. She was carrying 3,500 tons of coal from South Shields to Dunkirk. Half an hour later, those same crew of 20 sat in those same boats as they watched their own ship go down. Upright, today the Empress of Fort William sits at 24m and is 7m proud.

gassey- silverproudly made in Wigan silver award

- Posts : 5123

Join date : 2019-08-21

Age : 71

Location : Pemberton

Lolly likes this post

Re: Today in history

Re: Today in history

28 th February 1975

Moorgate tube crash :